When Abisola - a Nigerian woman living in London - began noticing purple-greyish patches forming across her arms, her GP dismissed them as stress-induced patches. After the symptoms worsened and spread to her face and scalp, she was finally referred to a dermatologist.

The diagnosis? Cutaneous lupus.

The delay in treatment wasn’t due to a lack of symptoms. Rather, it was due to a lack of recognition. On Abisola’s Black skin, the inflammation didn’t present in the typical “textbook” manner.

The curriculum of pale skin

People of colour frequently encounter a diagnostic blind spot. Most medical images, textbooks, and clinical guidelines are designed to help diagnose white skin. Dermatology education has long relied on visual cues, such as redness, which appear differently on darker skin tones. As a result, common skin conditions are misdiagnosed, diagnosed late, or not diagnosed at all.

The roots of this problem lie deep in the history of Western medicine. Dermatology as a specialty emerged in predominantly white populations, and early clinical teaching naturally reflected this. Over time, the failure to adapt to increasingly diverse societies created a stark disparity.

A study, led by dermatology professor Hao Feng, revealed that just 10% of illustrations in textbooks depict skin diseases on dark skin. The problem goes further than just teaching resources. Clinical research investigating the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 revealed the erasure of Black skin in dermatology practice.

“Our analysis demonstrates that articles describing the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively show clinical images from patients with lighter skin,” the authors reported. 47% of the board-certified dermatologists involved in the study even admitted to “insufficient exposure to patients with darker skin,” which hindered the quality of care they offer.

For generations of medical students and clinicians, the visual language of disease has been filtered almost entirely through pale skin.

Consider eczema, one of the most common inflammatory skin disorders. On white skin, it often appears as red and scaly patches. On dark skin, however, it presents as gray, ashen, or violaceous. The pattern repeats across a wide range of conditions: acne that leaves long-lasting dark spots, rosacea that doesn’t show characteristic redness, lupus rashes that appear purple instead of red, or even melanoma, which tends to develop in non-sun-exposed areas on people with darker skin. Simply because these presentations fall outside the narrow visual archetypes taught in training, they are overlooked.

Agents of change

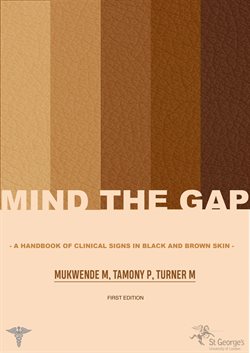

Grassroots projects have taken the lead in challenging the status quo. Mind the Gap is a handbook developed by Malone Mukwende, a UK-based medical student who became frustrated with the lack of representation in his studies. The resource features side-by-side images of conditions on light and dark skin, offering a visual corrective to generations of one-tone medical education.

Institutions are beginning to respond to such efforts. Some medical schools are updating curricula to incorporate skin of colour into dermatology training. The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology now encourages more representative image submissions and requires authors to report race and ethnicity when relevant. The Skin of Color Society is advocating for more inclusive research and practice guidelines, emphasizing that diversity in dermatological education isn’t optional - it’s essential.

Recognising the full spectrum of human skin is not a niche concern. The colour of your skin should never determine the accuracy of your diagnosis.

By Nnenna Ohaka

Subscribe to our newsletter to gain exclusive access to new articles and community initiatives. Stay informed and help us bridge The Science Gap!